Many people have witnessed the fabulous treasures that were recovered from King Tutankhamun’s tomb. Some of those artifacts have gone on traveling exhibitions that toured the world beginning in the 1970s (just ask Steve Martin); and the collection — including the famous gold funerary mask — is permanently housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Many people have witnessed the fabulous treasures that were recovered from King Tutankhamun’s tomb. Some of those artifacts have gone on traveling exhibitions that toured the world beginning in the 1970s (just ask Steve Martin); and the collection — including the famous gold funerary mask — is permanently housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

It’s comparatively rare to stand in the presence of King Tut himself. Unlike the stuff that was buried with him, the most legendary of all Egyptian monarchs still remains (in mummified form) in the subterranean chamber in which he was deposited following his death in 1323 B.C. That tomb can be found in the area known as the Valley of the Kings. My wanderings through Egypt in September 2012 included a visit to that valley, and the unique chance to gain an audience with King Tut.

A really upscale (and really old) cemetery

The Valley of the Kings is a sprawling necropolis on a desert plain on the west bank of the Nile River, near the city of Luxor and about 300 miles south of Cairo. In ancient times, the full name of the site was “The Great and Majestic Necropolis of the Millions of Years of the Pharaoh, Life, Strength, Health in The West of Thebes.” (Thebes, one of the largest and wealthiest cities in the Bronze Age world, was a precursor to Luxor.) This particular burial ground was quite exclusive; the only people laid to rest within its confines were kings and select noble personages. (Nearby is a separate Valley of the Queens, in which wives and children of pharaohs found eternal repose.) Its clients received accommodations befitting the stations they had occupied while alive; most of the tombs are voluminous and elaborately decorated.

The first corpse to be interred in the Valley of the Kings was probably that of Thutmosis I, who perished around 1500 B.C. The last tomb constructed at the site was built for Ramses XI, who passed away in 1078 or 1077 B.C., but it’s believed that he wasn’t buried in it.

Like the pyramids in Giza, the tombs were a tourist draw even in antiquity. Many of them contain graffiti scrawled by their ancient visitors; the earliest known such defacing dates all the way back to 278 B.C.

In modern times, all but one of the mummies recovered from the Valley of the Kings have been relocated to the Egyptian Museum. The exception, as mentioned above, is the mummy of King Tut, which is on display in his original tomb. It was famously unearthed in 1922 by an archaeological team led by Howard Carter.

In all, 63 tombs have been discovered in the Valley of the Kings. Not all of them are open to the public, as some are undergoing restoration. My tour group’s guide procured tickets for us to descend into four of the burial chambers: those belonging to Ramses IV, Ramses IX and Ramses III, plus, of course, the final resting place of Tutankhamun. So, yeah, on my itinerary were King Tut and three guys named Ramses. That’s not so surprising, though, considering that 11 different Egyptian kings were either named “Ramses” at birth or adopted that moniker as their coronation name.

Here’s what a typical entrance to one of the tombs looks like:

And I’m pleased to be able to share glimpses from inside a couple of the tombs:

It’s astonishing to me that the paintings in these tombs retain so much of their original colouration, thousands of years after the pigments were first applied onto the walls.

H-Bomb gets into trouble with authority — who’d have thought?

I would have liked to take more photographs inside the tombs, but even the pair of images that you see here was quite risky for me to obtain. Photography is strictly forbidden at the site, even when you’re just walking around outside the tombs. You’re not even allowed to bring a camera onto the grounds (photographic equipment is supposed to be checked at the entrance), but there’s a loophole big enough to fly an Airbus A380 through: you’re permitted to hold on to your cellphone, even though virtually all mobiles in use nowadays are cameraphones. I think you can see where I’m going with this. 🙂

In my view, the draconian anti-photography policy seems designed solely to coerce visitors into buying the books of postcards that are pushed upon visitors. I’m against coercion. Having no real choice in the matter, I did leave my “good” cameras behind on the tour bus; but my smartphone tagged along with me as my tour group proceeded to the tombs. Of course, I had to be careful to evade detection from the roving guards as I surreptitiously employed the “camera” app of my Motorola Droid 2 Global.

I was heartened to discover that I wasn’t the only member of my tour group who was engaging in covert picture-taking. I only learned this, though, as a result of the misfortune of one of my fellow travelers. Shane, an affable Australian, was caught snapping a photo with his cameraphone inside the tomb of Ramses IX. His excuse that he’d merely been using his phone to send text messages failed to persuade the guard. 🙂 Instead, the guard confiscated Shane’s phone and forced him to pay a bribe of 100 Egyptian pounds (about $16 US) to ransom it.

After Shane’s incident, I myself was caught engaging in the heinous crime of photography — and in the very same tomb! But my encounter with the guard who busted me had a happier outcome. By the time the sentry accosted me, I’d stashed my phone securely in my pocket. I wasn’t about to surrender it, and the guard understood this. He kept grabbing my wrist, and repeating some words in the Arabic language. Although I didn’t understand exactly what he was saying, his frustration transcended the language barrier. When I exited the tomb, he followed me out as I walked towards my tour guide, Ahmed. He warned Ahmed that if I was spotted taking any more photos, my phone would be confiscated.

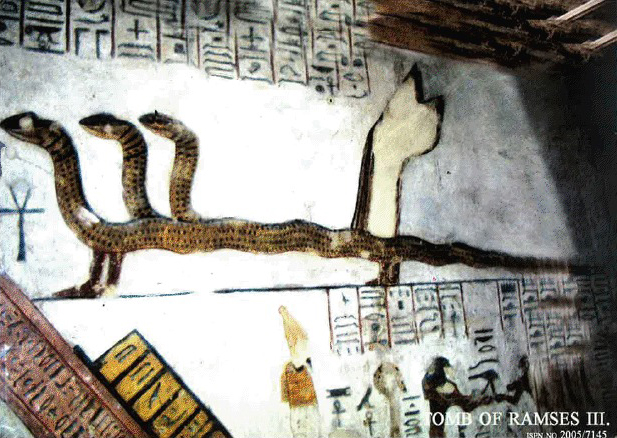

I didn’t risk any more photos inside the tombs after that close call. Here’s something that I would have captured on camera if I hadn’t been spooked by my confrontation with the guard: a painting of a three-headed snake, from inside the tomb of Ramses III. For purposes of this blog post, I had to settle for scanning in a postcard of that badass serpent, which was included in the book of postcards that I was pressured into buying:

Meeting King Tut

My visit to the Valley of the Kings culminated in my entry into the place of residence of King Tutankhamun.

King Tut’s tomb is small in comparison to the others at the Valley of the Kings. The reason for this is that its occupant died at age 18, after only 9 years on the throne, so not much work had yet been completed on the tomb before Tutankhamun needed to be sealed up in it. And by the way, when I think of what I was doing when I was 9 years old, it’s mind-blowing to me that a boy of that age could have become the ruler of an entire country — even though Egypt in the New Kingdom period was a vastly different time and place.

Because I was playing things safe at this point with my cameraphone, I have no photos of my own from inside King Tut’s tomb to show you. So I’ve done the next best thing: I’ve scanned a postcard of King Tut’s mummy from the postcard book that I purchased that day. It shows him as he appeared when Carter’s team gazed upon him in 1922, rather than his cleaned-up presentation today; but it’s the best that was available to me. 🙂

Coming face-to-face with King Tut (even if his face was under glass and in a reclining position) was as much of a transcendent experience for me as seeing the pyramids. To be able to do both of those things during the same vacation was spectacular beyond words. And since more than six months have now elapsed since my entrance into the boy-king’s lair, it’s probably safe to say that I successfully avoided the curse of the mummy!

Other nearby attractions

After exploring the Valley of the Kings, I’d already had a rewarding and memorable day. But before returning to our cruise ship, my tour group hit two other area attractions, each of which is notable and historically significant in its own right.

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut was the longest-reigning female Pharaoh, having ruled her country for some 22 years. Moreover, Egyptologist James Henry Breasted has called her “the first great woman in history of whom we are informed.” Her mortuary temple, the construction of which she oversaw, was erected in a striking setting. It’s situated under the cliffs at Deir el Bahari, on the west bank of the Nile near the Valley of the Kings. The temple bears the alternate name of “Djeser-Djeseru,” which I’ve seen translated as both “Holy of Holies” and “Splendour of Splendours.”

I liked the clean, elegant lines of the temple complex, and the way that the structure was carved into the sheer hillside:

Here’s what the temple looks like when you reach the top of all those stairs:

The Colossi of Memnon

The Colossi of Memnon are a pair of gigantic stone statues just across the Nile from Luxor. They were built circa 1350 B.C.

Both of the statues are meant to represent Amenhotep IV, the pharaoh who commissioned them. Including the platforms on which they’re placed, each statue stands about 18 meters (60 feet) high, and is estimated to weigh about 720 tons. Hewn out of sandstone, they originally stood at the entrance to a vast and magnificent temple complex, dedicated to Amenhotep IV, that exceeded even the legendary Temple of Karnak in size. But time has not been kind to Amenhotep’s temple, and these colossi are virtually all that remain of it. Their stupendous scale provides some idea of just how ginormous the temple that they adorned must have been.

In case you’re wondering about the colossi’s namesake, Memnon is a mythical Ethiopian king who is said to have led an army in the Trojan war. So how did the vanity project of an Egyptian ruler come to be named after a warrior from Greek mythology? Well, the story goes like this: An earthquake in 27 B.C. created a fissure in the northernmost of the two statues, which caused it to periodically emit a bell-like tone. That tone typically would be heard in the morning, for reasons having to do with the increase in temperature and humidity after sunrise. Memnon was the son of Eos, the Greek goddess of dawn. Due to his familial identification with daybreak, he himself became associated with the unique morning behaviour of the colossus. (The fateful earthquake was also responsible for the destruction of the temple that the colossi once accompanied).

The Colossi of Memnon, as well as the other ruins that I visited on a remarkable Saturday afternoon, are also evocative of dawn in another way. Ancient Egypt was among a handful of societies that marked the onset of what we think of as civilisation. You could say that it heralded the Breaking Dawn for human advancement and enlightenment, as well as for the flowering of artistic expression (of which the building arts are a part). One of the things I enjoyed most about visiting the Valley of the Kings and the other points of interest in the vicinity was the opportunity to journey backward into “deep time,” and to imagine what it would have been like to have lived during this watershed era.

Read the other parts of my continuing series on Egypt!

Prologue: Singing karaoke in Egypt

Part 1: Touring Cairo

Part 2: Touring Giza

Part 4: Touring Saqqara and Memphis

Click here to follow me on Twitter! And click here to follow me on Instagram!

Very good Harvey, your trip stories are always fun to read and well researched.

Shane (Mackay, Queensland, Australia) [18 Aussie dollars poorer after paying off the guard for my phone back.] Ironically I got a new Andriod phone when I got back to Australia, but have kept the phone that was held for ransom as a keepsake.

LikeLike

@Shane: Thanks for the compliments. Interesting choice of a keepsake (your phone)! But then, the best souvenirs are often the ones with unique memories attached to them, right?

LikeLike

Great article as always Harvey plus it brings back some great memories!

LikeLike